A Guest Post by George Kaplan

Clik here to view.

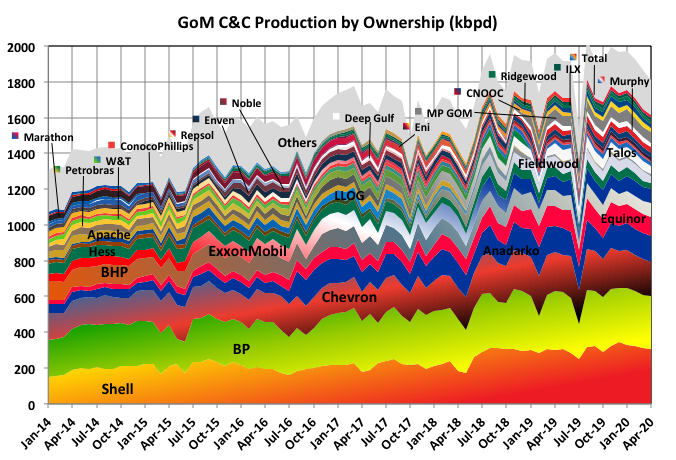

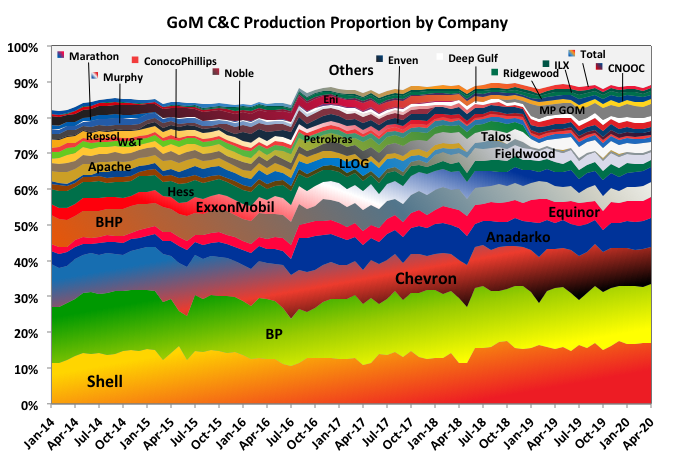

Production is dominated by major international companies particularly, and maybe surprisingly, European ones. Principally Shell and BP, but with Equinor, Eni, Total and Repsol also active and many are (or were) seemingly wanting to expand in the area. Maybe this is an example of reciprocal technology transfer: the North Sea was initially developed with a lot of American offshore know how and there it may now be the reverse is happening as deeper water fields using floating and subsea systems are developed.

Clik here to view.

The recent growth in production has come from the larger players, and they are taking a bigger slice of the expanding pie. The medium sized independents and smaller non-operating owners held many assets in shallow water but do not have the money, risk acceptance or knowledge to participate in the deep and ultra deep projects.

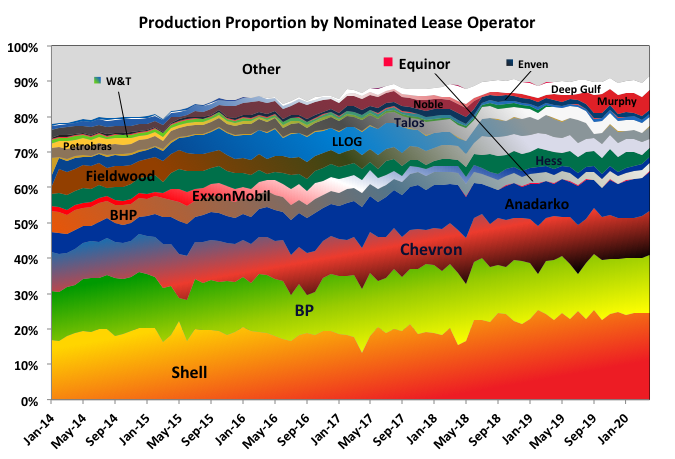

Lease Operatorship

Clik here to view.

Each lease has a nominated operator, and the proportion of production for each operator is shown. This is not the same as the operator of the surface processing platform for example Julia is a subsea lease operated by ExxonMobil but the fluids are processed in the Chevron operated Jack FPU. ExxonMobil provided the subsea control system that interfaces with the subsea wells and Chevron installed and now operates it. Operatorship of the leases is concentrated, and the proportion growing, amongst the major oil companies (shown), and still more so for the operations of the surface facilities.

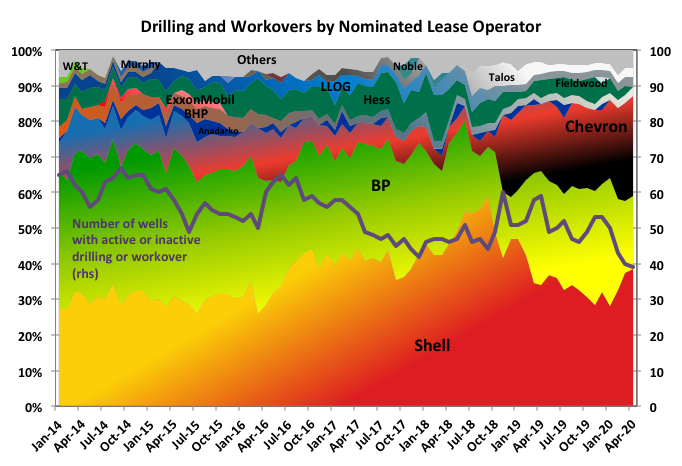

The big three operators dominate the drilling activity, which is now almost all deepwater, even more than they do production.

Clik here to view.

Reserve Holdings

Clik here to view.

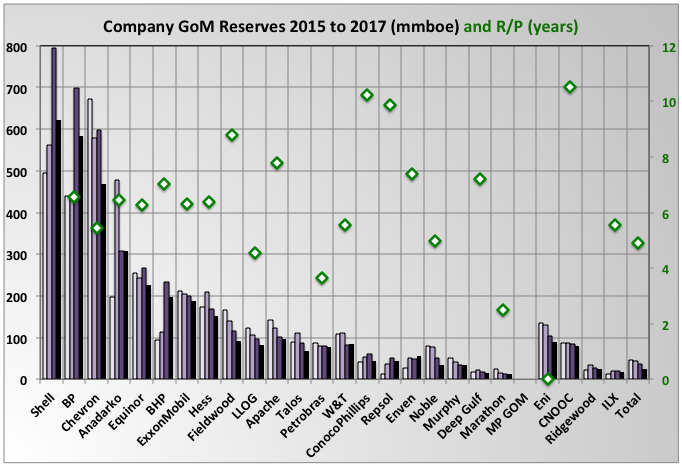

Reserves are concentrated among the larger players they also mostly show reserve growth (from brownfield growth I think), whereas the smaller companies mostly show decline. These figures are BOEM estimates and only go to 2018, but I think the trend would continue in 2019 as the projects announced for FID, and therefore that allow booking of reserves, are owned by the super majors. Lord knows what’s going to happen for 2020 though. Note that the numbers are more fuzzy even than the BOEM estimates as I don’t know how reserves are shared when a field is split across several leases with different ownership, so the best I could do was a simple equal pro-rationing of the field across each lease. The R/P numbers are around six to ten years but they change a lot from year to year. Only 2018 numbers are shown; in 2017 there was a clear trend of larger companies having higher R/P but that disappeared.

Company Liabilities

Clik here to view.

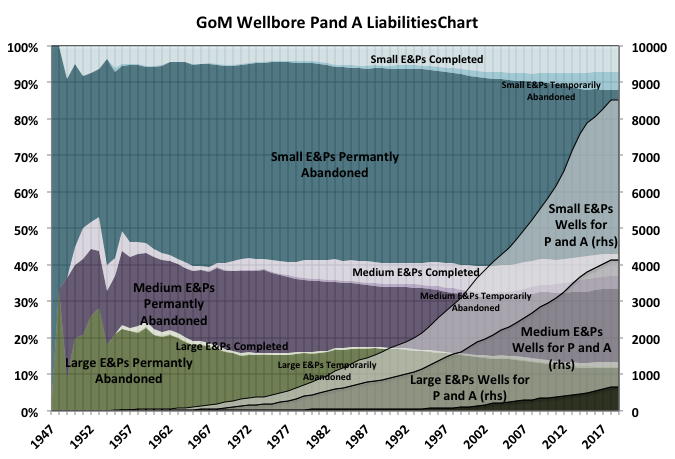

The large E&Ps keep up pretty well with their plug and abandon commitments for wellbores. They have a low proportion of temporary abandoned wells, although their number of completed and operating wells is growing because production is growing. Medium sized E&Ps, and still less the small independents are not; even as their proportion of operating wells fall their proportion of temporarily abandoned wells, and the total numbers of wells requiring future P&A are growing significantly. I think there is a good chance that many of these smaller operators will go bankrupt leaving a number of potentially leaking wells, presumably for the tax-payer to clean up (Fieldwood is quite a large company but with large liabilities – see below – and is leading the bankruptcy charge).

Clik here to view.

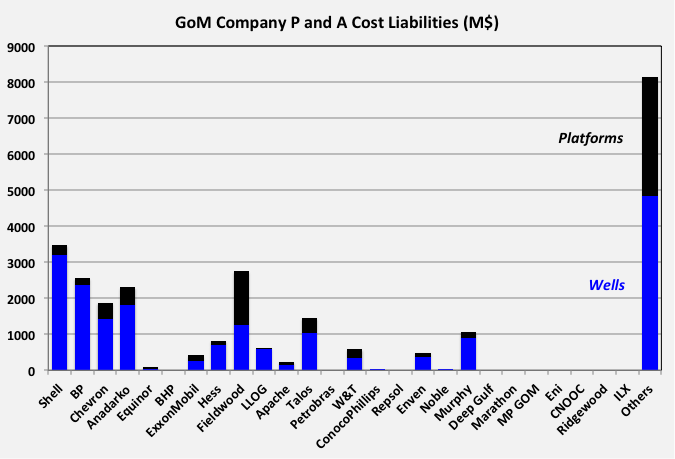

These liabilities are based on BOEM estimates and I’ve only added them based on the operatorship. In reality it is likely to be a lot more complicated with lease owners having to contribute so that more cost would devolve to the smaller companies. However the huge liabilities against “Others” is apparent. I’m not exactly sure how this would be included against the company’s net worth but it wouldn’t be a surprise if many were technically bust. The shallow water wells, which make up most of the inventory for the independents may be a bit easier to abandon, but there is no guarantee as they are not necessarily shorter and may require a MODU to access, whereas many of the deep-water platforms have dedicated rigs. Similarly floating deep-water production units are easier to remove than piled jackets.

Individual Companies

In the following charts the red band at the top of a companies production shows the total equivalent gas, pale blue at the bottom) is shallow C&C production, deep C&C is yellowy-green and ultra deep is greeny-blue. The more green for deep, and blue for ultra deep, the hue means the larger the present size of the field. Only the most significant fields in a company’s portfolio are named. The average line is the twelve-month trailing average for the combined production of the companies shown, and operatorship the combined operated lease production.

Shell

Clik here to view.

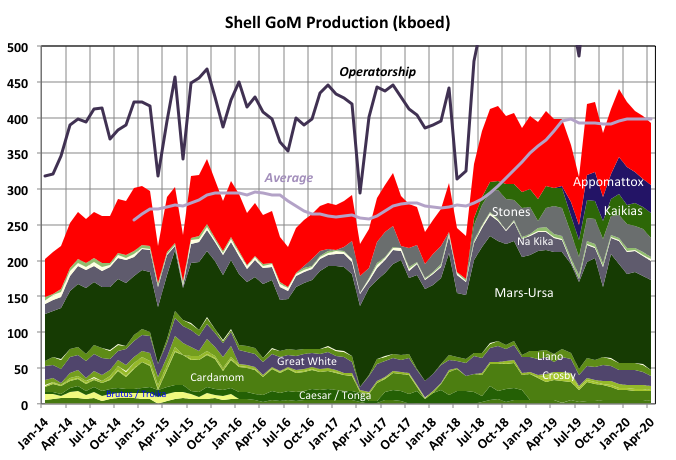

Shell is the biggest producer and operator, mostly thanks to Mars-Ursa, which is the biggest basin in the GoM. To date it has concentrated in deep water rather than ultra deep, but that is now changing as Appomattox continues to ramp up and with Vito due. Shell has a 60% ownership in Whale described as one of the decade’s largest discoveries in the Gulf, and expected to be a 100 kbpd development, even if it has been mooted as a tie back to Perdido and tie-backs that size are rare (in fact I don’t think I know of one). Shell has enough reserves, developments and prospects to stay top ad increase production even given the latest slow down.

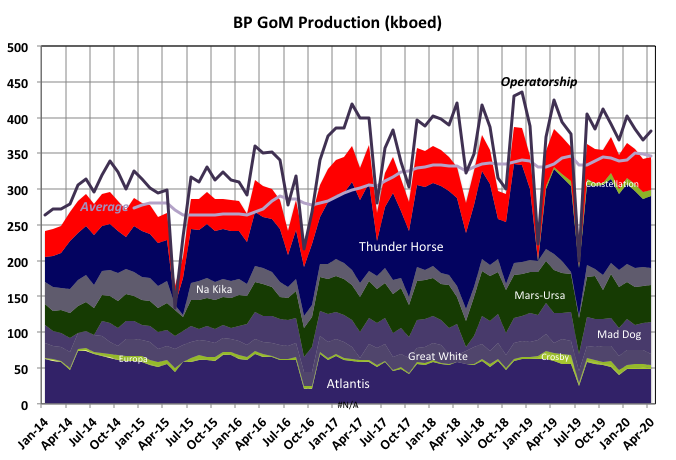

BP

Clik here to view.

BP is top dog in ultra-deep and is likely to keep expanding with Mad Dog II under development and Atlantis III in ramp-up. Mad Dog II (aka Argos) at one time had break even price of $80, the highest of the GoM prospects at the time by about $20. It was considerably simplified afterwards and costs have decreased but current economics must be marginal at best. Thunder Horse and Atlantis were something of disappointments initially but recent brownfield developments and in-fill drilling have continuously raised reserve values. Most of the super majors tend to sell off assets once the get to run down stage but BP does this more than most.

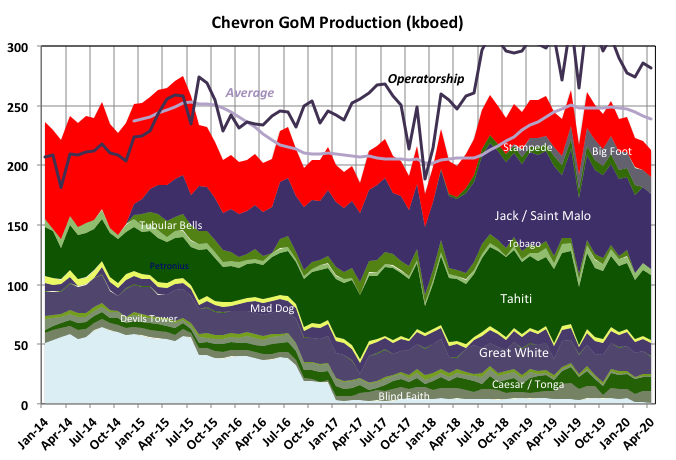

Chevron

Clik here to view.

Jack / St. Malo is the Chevron flagship, taking over from Tahiti. Both now seem to have completed the major development phases. Stampede and Big Foot are still ramping up.

At the end of 2019, when oil was still at $60, Chevron booked write downs of around $10 billion and stated that much of its deep water resource was not commercial at this price range, although I think most was not in the GoM. Chevron has significant undeveloped assets as operator at Anchor (in mid development), Ballymore (a qualified field in BOEM but with no FID until 2021 and the last news I saw was that it was planned as a tie-back to Blind Faith, which would tend to imply maximum production around 30 to 50 kbpd); and also has minority ownership in Shell’s Whale (no FID before 2021) and BP’s Mad Dog II . In December 2019 the IHS Upstream Capital Cost Index, a measure of development costs, was 180, down from 230 when oil prices were at their peak. Given a supply shortfall enough to cause a price spike it is likely this index would rise significantly, made worse by the loss of workforce through demographic changes and the two recent price crashes. Therefore prices of $100 or more could be required to make some of deep-water projects attractive again. Will this ever be seen – the camp that says the world economy can’t afford them seems to be winning at the moment, but maybe some kind of shale-like economic con or government intervention would allow it.

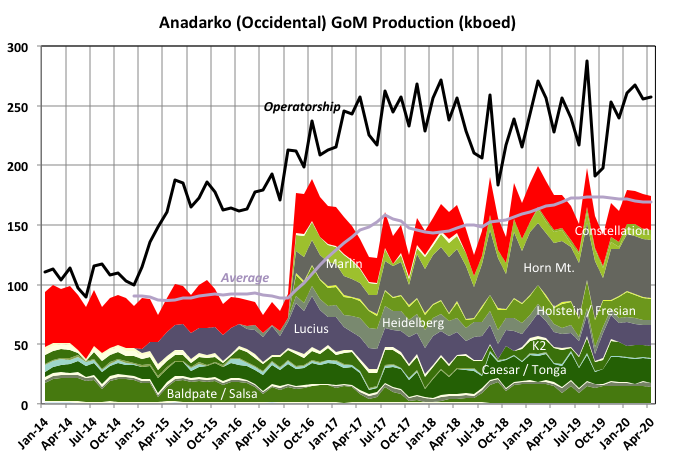

Occidental (ex-Anadarko)

Clik here to view.

Originally Anadarko had interests in deep-water fields with platforms operated by others. In 2016 Anadarko acquired and took over full operation of assets from Freeport-McMoran, which, in turn, had got them mostly from BP. It did completed several in-fill wells through 2018, which just about kept production increasing slightly, but that activity stopped and Anadarko mostly switched to share buy backs. Before that its two big new projects were Lucius and Heidelberg, neither of which, I think, has done quite as well as expected (originally there was a phase two planned at Heidelberg that seems to have faded away and Lucius processing system is more used for tie-backs: Buckskin, North Hadrian. Anadarko was taken over by Occidental before the current crash (though BOEM still have Anadarko as the operating entity) in what now looks like a bit of a nightmare deal. Occidental mostly wanted Anadarko’s shale holdings so their GoM assets might have been seen as a bit of a millstone even with $60 oil.

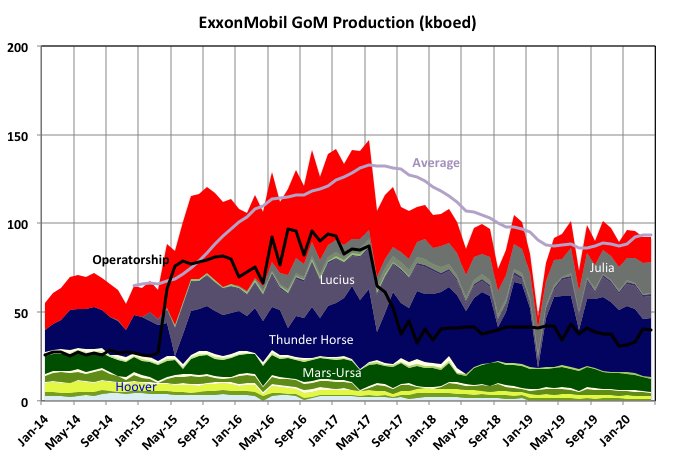

ExxonMobil

Clik here to view.

ExxonMobil would like to find a buyer for their GoM assets, but is probable going to be frustrated without dropping the price unrealistically or a sudden oil price spike. It operates a few leases, the largest producer is Julia; there has been talk of a Julia II expansion (larger than the original) but seems to have gone quiet – maybe waiting for spare capacity at the Jack floater. It had one of the original large deep-water projects at Lena but that has been abandoned over the last few years.

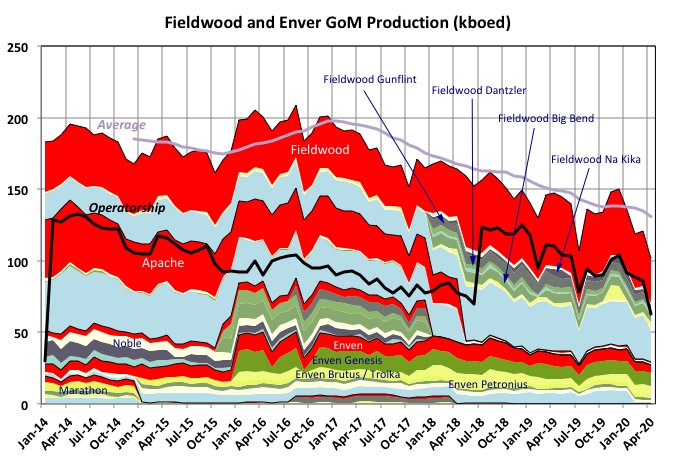

Fieldwood and Enven (Apache, Noble and Marathon)

Clik here to view.

Enven and Fieldwood are fairly new E&P companies with exclusive interest in the GoM. Fieldwood was formed during the irrational exuberance high price era in 2013 from Apache shallow water assets, with a lot of gas. It later took over the rest of Apache, and Sandridge and Noble assets in 2018. Production has been steadily falling and it declared bankruptcy in early August 2020 with $1.8 billion in debts and for the second time in two years). It has very high P and A liabilities for shallow water fields and a lot of end of life deep fields (all grouped in the pale yellow strips, which represent several similarly coloured lines) including Bullwinkle, which has the highest platform decommissioning costs. Its larger deep-water fields of Dantzler, Big Bend and Gunflint are all processed through the Thunder Hawk platform; combined they are over 50% depleted by BOEM reserve figures, unless there have been significant revisions since 2017, with Big Bend and Dantzler at end of life. It has operatorship of Katmai, a deep water field with 25kbpd design capacity and due this year. I don’t know how that will procede now.

Enven was also formed in 2014 and acquired assets from Shell, Eni and ExxonMobil through 2016 and took over Marathon Assets. It applied for an IPO in 2018 but withrew in February this year. Performance has not been impressive and it might be in the cue for the chopping block. It operates four old deep-water platforms, with interest in two others and doesn’t get involved in much greenfield exploration, but concentrates on near field low risk opportunities.

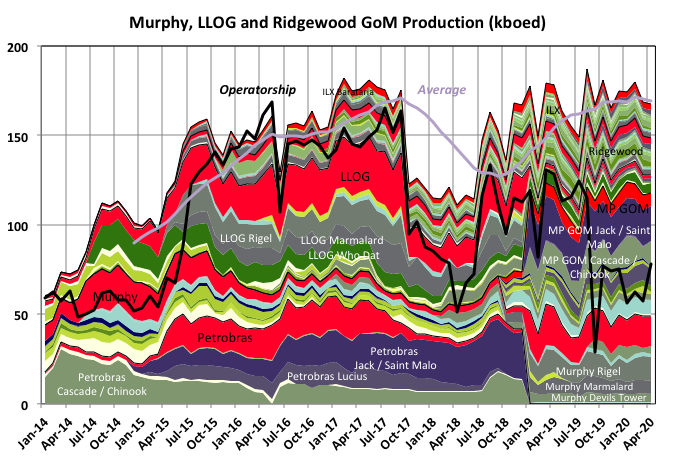

Murphy, LLOG and Ridgewood/ILX

Clik here to view.

Petrobras opted out of the GoM in 2019, selling up to mostly selling up to Murphy in a new venture, MP GOM, in which Murphy holds 80%; Murphy also took over operations. The Petrobras holdings in Cascade/Chinook and its Lucius were pretty disappointing and the Jack / St. Malo project, which has done well, has come to the end of its main development phases. Murphy also got a lot of assets from LLOG, including the development and operation of the 80 kbpd Kings Quay FPU. I wonder what the stake holders think of its expansion plans now. LLOG also sold their holdings in Shenandoah development (70 kbpd originally planned for 2024) to Blackstone, a fairly new private equity player in the GoM.

LLOG seems to have had a bit of a fire sale in early 2019 and it also sold a chunk of assets to Ridgewood/ILX. LLOG is privately owned so maybe the owners were cashing in but they also lost some income in 2017/2018 with a major failure in a subsea template at Delta House FPU. Ridgewood is a private equity company but also partly owns ILX with Riverstone Energy. Both entities concentrate on non-operated deep-water GoM developments, often they have independent holdings in the same leases,. LLOG concentrated on one or two well tie-backs and it looks like Ridgewood/ILX are continuing that way and have a number of prospects, though exploration may be delayed.

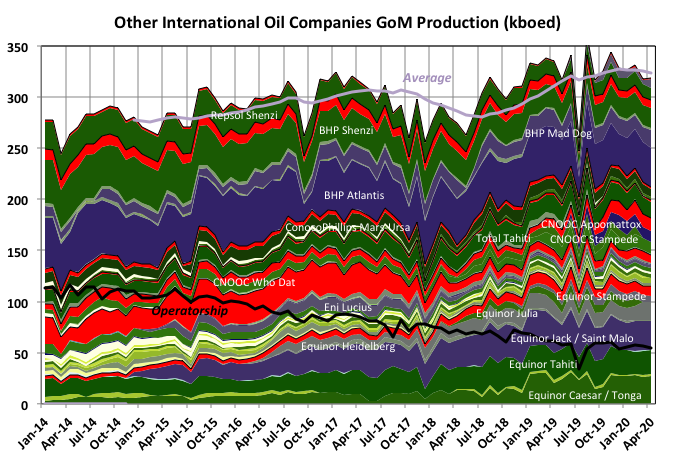

Other International Oil Companies (Equinor, Eni, CNOOC, Total, BHP and Repsol)

Clik here to view.

Equinor is a significant producer and expanding, proportionally, faster than any other, and that is likely to continue as it has holdings in Stampede and Big Foot (still ramping up), Vito (in development) and North Platte (in FEED). It does not operate leases or platforms.

Eni looks to be fading away, it owned a part of some small recent tiebacks but nothing planned

CNOOC, which used to be Nexen, was trying to pull out of GoM activities in 2018 because of the Trump trade wars but haven’t done so and are unlikely to find a buyer at the moment.

Total is a small but ambitious producer and will grow as it has 37% of Anchor (80 kboed, due in 2024, but may be delayed) and 60% of North Platte, for which it will be operator (80 kboed in delayed FEED and with 20 ksi completions, like Anchor).

ConocoPhilips is a small producer and would probably like to sell up if possible.

BHP is a significant but declining producer and a couple of years ago there was talk of shareholders agitation to sell up.

Repsol has an agreement with LLOG to develop Leon and Moccasin as tiebacks. They co-operated on the similar Buckskin project, which, like these two, was originally thought to be a larger field.

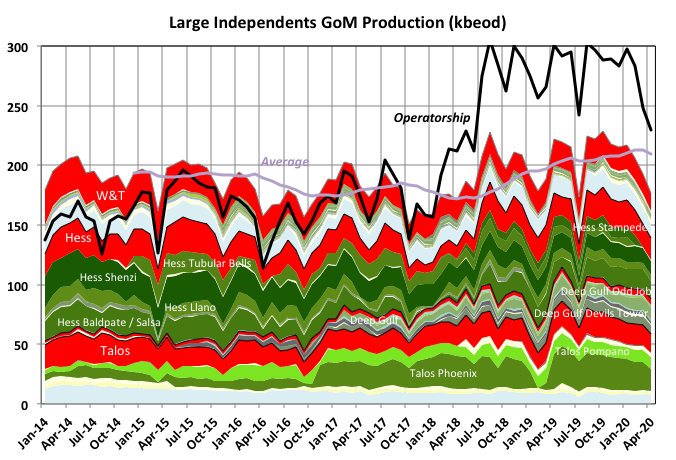

Other Large Independents (Talos, Hess, Deep Gulf and W&T)

Clik here to view.

Most of the assets of these independents are in decline with nothing much new on the horizon. Deep Gulf, owned by Kosmos since 2018, and Talos, which took over Stone in 2018 and Castex in August this year, have expanded slightly recently, Hess stayed about level (but I think was trying to sell some assets to fund developments offshore Guyana) and W&T is mostly in shallow water. These sorts of companies tend to go for short cycle, high margin projects, and economics and geology are militating against those at the moment (and for the near future). Combined these companies lost over $700 million in the second quarter (though only W&T is exclusive in the GoM, and Talos mostly there). I’d imagine all are suffering with debt. Hess operates Tubular Bells, tied back to the Williams FPS, Gulfstar. It was supposed to be the anchor field for the platform, to be followed by other tiebacks; there was a small discovery and single well tieback this year, which is counted against the Tubular Bells field, but I don’t know of any other prospects.

Off Topic Finish: Denial

There’s a recent theory that an ability for denial is evolutionary adaptive in a cognitive species and was necessary (even if not sufficient) for us to become the dominant homo species. The theory goes that without it we’d understand just how horrible life and death can and will be, descend into a “slough of despond” and stop struggling to reproduce. I think the jury’s out on that, and don’t know how it could be demonstrated. It feels a bit “just so”-ish but nevertheless there’s a lot of denial about and its prevalence seems to grow, or at least becomes more overt, as things get worse. It looks like a battle of short term freeze-flight-fight – mostly freeze maybe – response from the reptile brain, mainly the amygdala (mostly dominant in conservatives) and longer term problem solving, planning, logic and post-rationalisation from the mammalian side (mainly the anterior pre-frontal cortex, more influential in liberals). If you want to argue the politics then one notable result is that someone’s voting preference can be predicted with a high level of accuracy just from an MRI brain scan (over 85% from memory; it’s somewhere in Behave by Sapolsky, which I highly recommend, but it’s a long book with small print and smaller footnotes).

The most obvious form at the moment is climate change denial and it is strong evidence of denialism’s dominance that however much the accelerating tide of evidence sweeps all before it the die-hards remain completely refractory, albeit subtly changing their arguments as each is successively knocked down. However there are plenty of other trends threatening civilization and possibly the human race that have their own deniers, often, but not necessarily, overlapping with the WUWT gang. Take your pick from biodiversity loss, water shortages, new pathogens for humans or crops, resource depletion, soil erosion, financial crises, secular development cycles, AI, demagoguery, overpopulation etc. They all have potential to take big lumps out of our collective wellbeing, they are all pretty well advanced and the combined probabilities and consequences are much more than the sum of their individual risks.

There are two often-cited future scenarios that I find particularly bothersome. One is the technocopian dream that we transform to a shiny Star Trek like future and the other that we can achieve a localised, sustainable bucolic idyll (more Star Wars maybe). They both have a tacit assumption that such transformations would see the end of all our major problems. It’s a kind of humanist eschatology that I find as delusional as organized religions and more distasteful than a few (though not the monotheistic ones).

Denial, to some degree, often comes in because someone knows all the risks in their particular field but is ignorant of the issues involved in any solutions – usually because they involve many other, unrelated fields. For example a typical climate change paper on causes and environmental effects, written by a scientist, or one concerning the societal consequences, written by an economist, sociologist or similar, will have a load of details on the actual subject, and then right at the end something like “we just need to get off fossil fuels in X years, but time is getting short” (as it has for the last forty years).

I can’t believe any of these authors have ever been even peripherally involved in a multi-billion, multi-disciplined engineering project. These are difficult at the best of times and invariably overrun schedule and cost estimates. What turns them into complete disasters is everything that we face in trying to switch to “renewable” energy: a tight schedule because it “has” to be; engineering with technology that has not been properly tested and proved at large scale (e.g. CCS); an environment in which the equipment supply base has to expand rapidly and virtually in step with the demand; rapidly increasing requirements for trained personnel; project management teams with management experience in unrelated industries or only technical experience in the relevant industry; a huge demand for trades people during the construction phases so they can up sticks whenever a new, and longer lasting, contract becomes available; the need to work in undeveloped countries with poor infrastructure, untrained staff and corruption; constant planning issues; social disruption and unrest; inevitable extensive state and political interference (not limited to regulatory oversight which states do best); financing issues; etc. There is a saying in large projects: quality, schedule or cost – pick any two. But when there are a few detrimental influences as above you are lucky to get any of them. Usually after lots of rework and delay something near to minimum quality will be met and with luck there will never be an incident that tests the design at its weakest limits.

Especially, it is almost impossible to do any of these large projects in widespread and prolonged volatile geopolitical environments; and you only have to look at USA/Hong Kong/Lebanon/Belarus/ Middle East (pretty much anywhere)/Libya/Brazil/Bolivia/Chile/Venezuela/Kashmir etc. to see that is only going to get worse. Climate disasters (see Asian flooding to come or South East USA if the hurricane season is as bad as predicted) and food shortages (see Lebanon in a couple of weeks) make thinking more short term and unrest more damaging. In almost every revolution the “newly liberated” peoples end up initially, and for some time, worse off than before.

There is a hydroelectric development project in Labrador which offers a salient lesson – it was forced through partly as a political statement when there were better alternatives, the management team were locals (also a political decision) mostly from the oil industry with no hydroelectric experience; add a few harsh environmental issues that hadn’t been sufficiently allowed for during planning, many contractual issues especially as insufficient contingency had been included, and most recently Covid19. At last count the price had doubled (to over $12 billion) has virtually run out of contingency (again) but still has considerable downside risk. It is two or three years late and counting, and the electricity produced is going to be very costly. There was a large enquiry completed last year that had fingers pointed in all directions. That was a one off multi-billion, multi-year project, done when there were few limits on workforce availability. Switching fuel sources (especially when it is forced rather than a natural progression to “better” ones) is a continuous, global, multi-trillion, multi-decade effort and would consequently have far more ways to go completely off the rails.

It’s often said that we need an Apollo or Manhattan project, but what is needed is nothing like those which involved small teams of dedicated and appropriate personnel, with unlimited resources producing compact one off devises. I’m not sure it’s much like the WWII mobilization either, that just had one relatively short term problem to solve, and there wasn’t much thought given to what was going to be done after victory.

The second idealised future is the sustainable, localised rural retreat type, often coming from ecologists or liberal leaning sociologists and journalists. It seems to me that would involve some kind of giant social engineering project, it might work with a hive species with common DNA, but even then I doubt it on a global basis. The proponents seem to think that once shown the error of their ways everyone is going to behave just like themselves, or at least like they are told to. They seem not to get that people’s behaviour is not logic driven but by ancient hormonal reward pathways, status signaling, dynamic tit-for-tat etc.

I’m a bit out of my comfort zone with philosophy but I think there is a concept of ethos (which I’d associate with our reptile brain) that is a culture’s spiritual base, and eidos (the mammal part) that is its logical and intellectual character. The proponents are relying on changing the global eidos, but ethos is always going to win and will always prioritise the short-term self-interests and reproductive rights of the elites. One theory of how this sea-change is supposed to happen is through cultural evolution, which can occur much faster than the ecological type. But the nature of evolution is stochastic; every event is random and localized (I think they would be called Markov chains, but my memory is going for a lot of mathematical things). Evolution has no sense of objective “improvement” and can’t be directed, so I don’t see how this can be expected to lead to any sort of sustainable arcadia.

I don’t see much chance of retaining any sort of even medium scale civilizations, though the decline might take a long time and, for most, an increasingly unpleasant one (another common denial is the “by 2100” one, which kind of implies that any bad trends stop at that magical date, maybe that’s when the humanist rapture is expected). The trouble is the longer and larger the overshoot is allowed to become the bigger and deeper the collapse. Catton, in the book Overshoot, admittedly on a fairly limited sample size, indicates that, following collapse, the undershoot is of the same order as the overshoot, and if deep enough the species goes extinct. If, after the main population drop, all that is left is a collection of isolated and genetically bottlenecked tribes then it’s easy to see how each could be wiped out from separate and random events (pathogens, drought, crop disease, strife, genetic disorders etc.) especially in a wrecked environment that would still be changing at a rate that is orders of magnitude faster than any evolution processes could keep up with.

Common advice is to do something positive even if you feel things are hopeless, which is fair enough but I think still smacks of a large amount of denial. “Armageddon, it been in effect, step … c’mon, let’s crank this shit up and get busy,” (Professor Griff). Words to live by.

End of rant

The opinions expressed in this post are those of the author. They do not purport to reflect the opinions or views of PeakOilBarrel owners or other contributors, or those on any of the other sites that may choose to download and repeat this post, whether with or, as always, without permission (please feel free, but only if you take all of it).